The interviews, research, and development of this piece were done in the week of Monday, July 27, 2020—almost a week before Beirut’s most horrific explosion in history. Mourning the hundreds of lives lost, thousands of houses obliterated, and the millions of souls taken by the system to this date, may this piece be a constant reminder of the many open hearts this city carried—and still carries.

Even though Lebanon’s October 17 uprisings were positioned as a collective force to terminate money-hungry governance, corrupt ‘leadership’ and colonial, sectarian, racist, and sexist constructs, real impact can be found in what was created in the process. From protest squares to marching streets, the uprising reclaimed public spaces (some for a short while), enabling us to visualize a healthy public life. From discussion circles to alternative media, the uprising reclaimed public voice, emerging with new perspectives on the rigid dying systems that were set in place for us. A few of the plethora of revolutionary impact you can realize following that logic.

The leftfield Lebanese music scene was at the forefront of revolutionizing thought and culture at many pivotal moments in its rather young history, but like all revolutionary concepts today, it is crippled by the financial and physical strains of the current moment, all while facing a question of life or death. As the seeds of the future are buried in the belly of our present, I was guided on a journey exploring the rich past of this scene and evaluating its mind-bending present; in hopes of constructing the future we might need to be in.

Tamara Saade “City full of Characters” 01-05-2018

We’ve never had the proper infrastructure. Agents, promoters, managers, venues—none of that.

Ziad Nawfal mentions as he takes a retrospective dive into some twenty-thirty years of experience in the music scene as a veteran collector, radio host, DJ, promoter, and overall artist. He explains how the lack of infrastructure created a physical and financial toll on the live music experience. This grave lack impacts the creation and facilitation of the scene on multiple levels, from the most tedious tasks in the process of organizing a live show to big picture decision making. “It’s endearing at first—every scene faces these struggles in the early years of creation.” Retelling his experiences in the early years of organizing the experimental festival IRTIJAL along with Sharif Sehnaoui, Mazen Kerbaj, and Raed Yassin back in 2013, Ziad continued “You know (we’d say) the festival doesn’t have to make money, we’ll pay from our own pockets, the artists can sleep in our own beds, we’ll use our own cars…” Then as the gaps in infrastructure kept on growing wider, the lack of sustainability became a stifling concern to many artists & promoters. Ziad ran through a list of live music ventures that were hindered or even halted due to a lack of support, from ventures rooted in the scene’s past like The Basement and Club Social, to ventures of our rather recent time the likes of Beirut Open Space, Wickerpark Festival, and Irtijal. Of course, in this capitalist world, all these structural problems eventually embodied themselves as financial losses, where venues weren’t able to sustain a live music scene so they became bar/venue hybrids, promoters often found themselves paying losses from their own pockets, and artist revenue streams diminished by the day.

“…(these financial shortcomings) kept happening as recently as last year where at the end of one particular event organized by Ruptured, we had to step out of the venue and take money out of our personal bank accounts to pay the DJ’s, and that’s just one silly example. You can’t say stuff like that shouldn’t happen, because that’s the nature of Beirut and the country we live in, but stuff like that shouldn’t have happened anymore. ”

Put on Your Red Shoes” event poster 15/3/2019

This lack of infrastructure tells you as much about the structural and institutional shortcomings of the scene, as it tells you about that of the city that harbors it. To be able to understand the music, a byproduct, we need to reflect upon the environment it was born in. This issue feels more like a dichotomy, especially in the process of creation. Lebanese and Arab artists often get stuck between reflecting on and running away from their environments in the music. However, exploring music rooted in its contextual reality came naturally to one rapper who eventually became one of the main drivers in the Arab Rap scene. Perhaps because of his journey from journalism to rap, or perhaps due to the grassroots nature of his genre.

Mazen El Sayed a.k.a El Rass, one of the dominant veteran figures in the Arabic rap scene, explains how futile would be our attempt to analyze the music or the scene apart from their socio-political undertones. Reading the scene apolitically is not only impossible but also creates a dissonance in our cultural mechanism—Mazen recounts how this disconnection from reality skews, if not destroys, our cultural development. He explains how hollow promotable headlines have been a form of escapism deeply grained in this disconnection; it was either the over-chewed narrative of Lebanon being a cultural and touristic hub that sugarcoated the rotting systems at its core, or pseudo-nationalist conservative rhetoric, performed by the likes of Georges Khabbaz, that stood in the way of real communal building.

“It actually created a separate market—a market for ‘socially-involved’ art without any form of real social involvement or real cultural added value. This idea that Lebanon is supposedly blessed with more liberties and freedoms than our neighbors—what should this freedom really mean? (Real freedom) is that you are free to rebottle all of these ‘liberal’ notions that have been on repeat for no less than 50 years.”

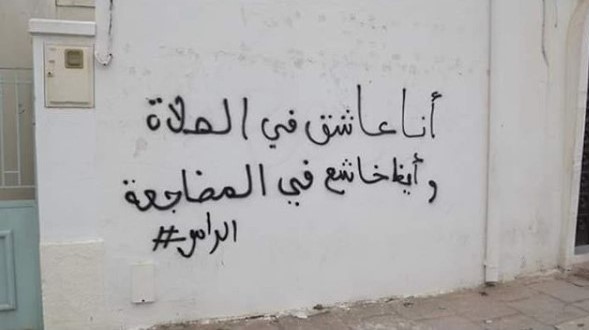

El Rass lines grafitied on walls in Tunis, 2013

These narratives that feed into our dominant socio-political system control the mainstream and institutionalize themselves in the alternative scene (and the latter could be harder to spot, rectify, or undo). Even though in Mazen’s opinion, the total collapse of our financial and political system did not bring forth any new realities, it could be an opportunity to spot the larvae left in our music and communities by classist & capitalist locusts.

In a quick overview of the Arabic rap scene, Mazen spotted many examples of some sort of popified mainstream, where rappers and artists have become an extension of the very systems we’re fighting. He stressed the importance of understanding the ideological direction of our artists, even the lack of one, because a lack of ideological direction is a direction in on its own, and it’s that of the market.

The market is not driven by ideology it is driven by the balance of ‘value‘—and that favors a certain group of people: the ones who have the most impact on the market, the people and powers that can shape it.

To all those who have written and still write about how Beirut is the city of contradictions, it’s time to realize that the city is, in fact, a land of contradicting realities. These realities overlap, create, and destroy each other almost viciously. So perhaps in apocalyptic times like these, it could be helpful to ask ourselves which reality we are subscribing to, and which are we succumbing to.

Tamara Saade “Beirut Sweeps” 05-08-2020

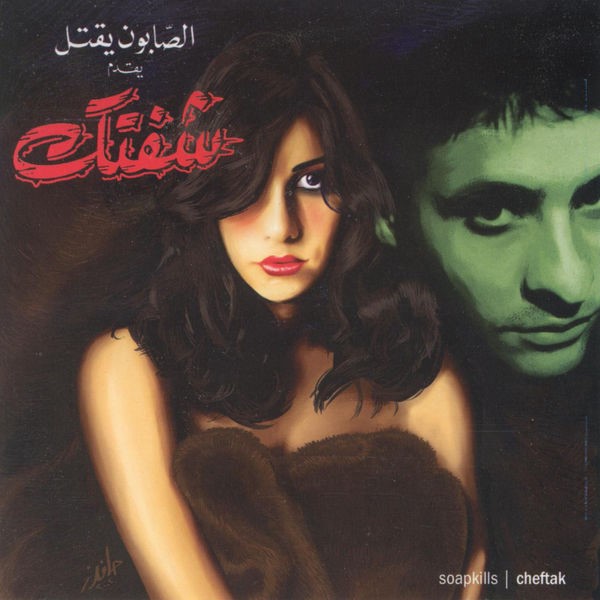

At a local bar in Achrafieh, a residential area in the east of Beirut, a local band was unveiling what was soon to be an unstoppable reality. Soapkills, formed by artists Zeid Hamdan and Yasmine Hamdan, was performing for the first time in the early ’90s. Amongst a DIY setup of faulty mics, bad wiring, and a shabby DJ mixer to plug in all equipment, the duo was about to change their lives and the lives of the many artists who took in their footsteps across the region and around the world.

“Soapkills happened at a time when people were hungry for something to bite on, literally and figuratively. In a sense, it was completely unpredictable, but at the same time, something needed to happen to draw the current music scene at the time out of its apathy.“

Nawfal reflects upon the Soapkills experience, on how from the day he received their demos or facilitated their first show it was obvious that there was something unique about the duo. He specifically remembers the rarity of their first few concerts in the early ’90s where there was little to no production, basic sound setups, and definitely no likes of Fadi Tabbal (from Tunefork Studios) on sound engineering (as he puts it)—still it was nothing like he’d ever seen at the time.

Soapkills “Cheftak” Album Cover

Choosing Soapkills when asked about the relevant music movements or periods of our past, Ziad felt it was important to redefine what that really meant. “They’re more like bubbles of activity, usually centered around a person or a group of people… round objects that crisscross and interfere with each other or stay away.” These bubbles or circles of activity tend to not only gravitate around the same people but also attract the same audiences as well. Considering the relatively small size of the scene and the country, the lack of sufficient interconnectivity could be natural as artists’ first impulse is to gravitate around their peers or the circles they feel comfortable with, or it could be a red flag on the nature of our music communities. After 10 years of being an independent artist, El Rass stressed the vital role that the communities around him or abroad played in his survival and gradual growth as much as he shared his frustration with what he calls a crisis in collective work.

“I say this with a lot of bitterness—it’s been 10 years that I’ve been trying to build this (a collective approach to cultural production).” El Rass expressed his disappointment in the lack of urge for collective work where artists, promoters, audiences, and community members have not been able to coordinate, strategize, or work together for a collective product. Inflated egos, unjustifiable insecurities, or simply lack of group/collective mentality does not necessarily hinder the outcome of the scene per se, but it does stop it from achieving its true full potential. Almwaten101, El Rass’s latest collaborative project with Paris-based Syrian rapper/producer Jundi Majhul could be the closest example of said collective cultural production. “I had a gig in Barcelona, I was done with it, the next one in the tour was in Marseille, but they were 6 days apart. I called up Khairy [Jundi] and asked if he was down to make music and it was a sure thing. I got to his place and we had 5 days—five days, five tracks. We’d wake up in the morning, make music all day, then PlayStation at night… I rarely had these musical experiences throughout my entire career.”

Granted, the conditions of this serendipity were conducive, somewhat preferred, which limits it from being a parallel or a reference to our situation back home: if it’s the infrastructure we’re fighting, our city has witnessed heavy hits in the form of closures of many a cultural space. If it’s the financial situation we’re fighting, our market fluctuations are now a riddle for the toughest of economists around the world. If it’s the gaps we need to bridge between artists, collectives, and communities, how would that scale to social distancing requirements?

But this kind of work, as Mazen puts it, needs a form of dedication or rather of sincerity; and that the individuals who can do this collectively, do so only because they have taught themselves how to do it alone. El Rass addresses the collapsing elephants in the city:

This is the context that we should supposedly start from. We know the social dynamics are against us, we know that the economic context is against us; but this can never be included in our discourse, even within ourselves, as an excuse for us not to do what we need to do.

The line “Do what you need to do” always rings a bell in my ear, it signifies a very dire situation no matter what context it was thrown in. It also speaks of a certain type of hunger, a mix of bitter, brave, and broken feelings that harnesses a power to fight. This power, however, is fleeting and if not invested properly, could result in famine. Two conflicting realities the entire nation knows all too well at this point. This hunger is surely found in the local music scene in all its circles, from the Experimental (in the broad essence of the term), Electronic, indie, to the rap scene. If we reflect on only the past few months dating back to early February, we can hear some heavy-duty noise. From album releases like Murur Al Kiram by Kinematik on Ruptured or EL Rass’s independently-released Almwaten101, to a cunning local compilation by Diggers Delight record label featuring names like Jad Taleb, Jack the Fish (reinvented as Bakisa), Ribal Rayess, Audioblend, and Pomme Rouge. The DJ/Producers and the devilish duo are expected to release their debut EP “First Bite” on Thawra Records early August, the label which in itself was founded by Electronic artist ETYEN back in April. Amidst a quick and deceitful reopening of the country in early July, Indie artist Paola Ibrahim even managed to showcase her debut solo show as Pól for a live audience.

This is only a brief overview not meant to exclude any of the valuable music releases, or the many bands, labels, and artists who streamed to the entire world this quarantine season, including in Insta Live music festivals like BJSFEST.

Reflecting on what could be driving this noise-making hunger in the scene, Ziad explores the dynamic with artists he works or interacts with: “I think some of the more interesting aspects of the musicians that I work/have worked with is their generosity on one hand, and their willingness to experiment and be open to one another—which I find absolutely astounding.” He then continues to express a recent willingness to collaborate, or at least a form of opening up for experimentation between artists “from all walks of life”, as he puts it. He mentions live music experimentations between Mme Chandelier, Jawad Nawfal a.k.a Munma (who also has been releasing his collaborations with various artists on his recently founded label VV-VA), and Fadi Tabbal—a combination he finds peculiar. Examples of an established Dream Pop trio like Postcards backing up multi-artist Serge Yared, or member Marwan Tohme guest guitaring for the anomalous Flugen also surfaced. This is not to forget rare music collaborations that resulted in incredible cultural productions like: Zeid Hamdan and Lynn Adib with Bedouin Burger, classic records like Jade’s “Jack” being released on genres-curious Thawra Records, or Frequent Defect’s Rise 1969 on a Judas Mordache track. Nawfal recounts how all of these unexpected collaborations have in fact happened, and while some were organic, most required a driving force or an initiator. Even though early signs of these initiatives are visible, they are still not as present as they should be, Ziad concludes his reflection:

There’s also reluctance. Musicians are moody characters and (yes) there’s a lot of ego involved. For every super generous, super curious gesture or venture, you get the opposite; you get someone who doesn’t show up… it has a lot to do with how small the scene is, and how easy it is to get disillusioned.

From the disillusionment of realizing that you never really sustained a real following when your storm of clout starts blowing down, to the more genuine disillusionments of not getting the feedback you expected from a crowd. The real damaging ones, though, are the disillusionments rooted in what El Rass and Hip-Hop practitioners refer to as ‘temptation’. Mazen talks about how brutal and more present than ever temptation in the Arabic Rap scene is, as he critiques a recent Rap feature that really sounded the alarms for him. The track in question included a feature by a mercenary of the Assad Regime, a clout stunt so damaging it opened the door for rappers and audiences to interact with and normalize a paid fighter for the regime.

“We fought for this shit, we know people that died for this shit—and we still are… (before) we weren’t just selling slogans to people because it was the right moment to do so” El Rass expressed his shock and disdain with artists and audiences condoning such productions. Mazen continues to apart the reality behind such attempts, as he stressed that compromises like these are driven by temptations like numbers on boards, fame, or quick cheques. If the scene has been infected with temptation and we are to intervene, El Rass did formulate a practical proposition.

If we all stick to our shit, and we actually coordinate and consolidate with each other, we’ll have the strength to get all of this without having to compromise.

This was in part what Mazen meant in his latest piece published in Ma3azef when he wrote: “We either produce together, or we die separately.” El Rass, later on, shared his ideal image of the collective: a group of people who resonate their energies in building the same wave, who sit together to express, manage, and develop their expectations. Simply artists and craftspeople who are able to produce and develop cultural products that create wealth and expand the horizons of everyone actively involved in the process. In a sense, this was not just his call for reflection, but it could also be considered his call to organize.

There’s a lot of noise coming from the city, but there is also a deafening silence. Lurking between the lightless streets of a nation on lockdown is a clash of realities. Ziad tells the story of a local alternative scene, that in his case could fill 15 minutes of radio air time at first, growing to 30 minutes, then full hour sets of strictly local music (with a definition of local as supple and transborder as it should be.) He was always one to unearth golden talent and eclectic sound, hold it up against light for the world to hear, making a career out of his local affinity. As he struggles with the financial and logistical calamities of trying to run the label or sustain a radio show in times like ours, Ziad ponders upon an almost eerily uncertain future. Looking back at these conversations, I’ve been contemplating the realities I’m surrounded with on the daily and their complex relationship with the ones I’m subscribed to in my head and on my playlists. A relationship almost identical to that of hunger and famine. As a final open door, Architect of Arab rap El Rass also leaves us with some realities to question:

I had to start from the realization that in order to achieve half of what the others have achieved, I needed to work a 100 times harder… you either say I’ll work a hundred times harder, and fight their (the people of power) privileges at the same time, or you’ll plead the eternal victim and waste your entire time worrying about how harder it is for you.

As I read this line and reflect upon the many apocalyptic pressures of Lebanon and the region I can’t but remember a couple K-Lamar lines from his disruption on the track “i” which I shall leave you with.

“we aint got time to waste time my N****…..The judge make time, you know that, the Judge make time right?”

researched & developed by Majd Shidiac, Edited by Yara Mrad