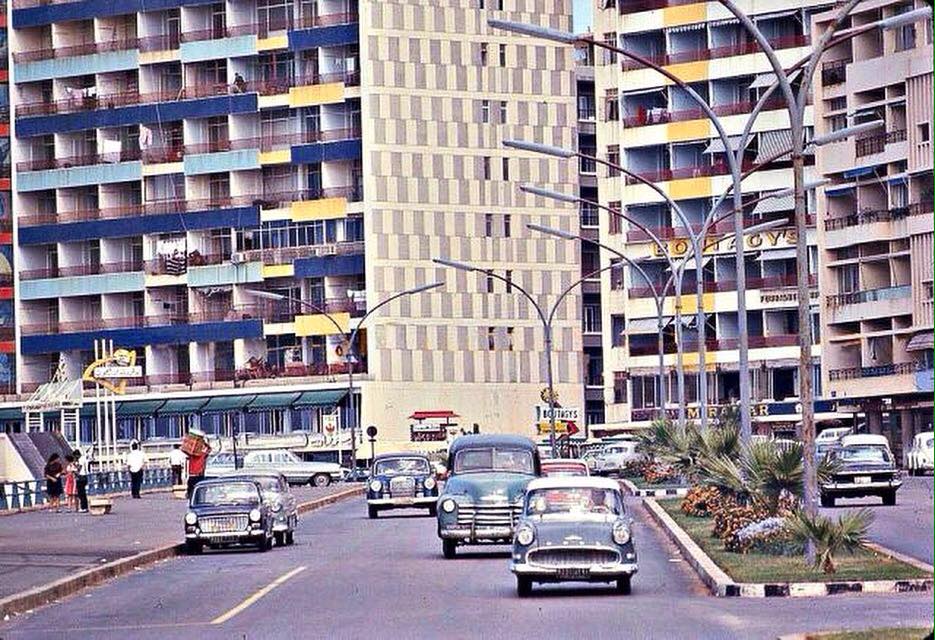

Just a few years before a 15-year civil war plunged Beirut into absolute chaos, Lebanon’s capital was a hotspot for the Arab world’s golden age musicians, a sort of Paris for the Lost Generation. That era saw the birth and demise of the careers of many great artists, some of whom subsequently saw their name fade into oblivion. One woman, Dounia Younis, better known as the “Lebanese mountain singer” for music aficionados around the world, had a promising run in the 1960s and 1970s, singing with legends such as Zaki Nassif and Wadih El Safi. Dounia’s career ended abruptly as she had to choose between love and art, but her legacy lasted long after she stopped singing, and far beyond Lebanon and the Middle East.

This is the story of a woman whose magical voice captivated the ears of ethnomusicologists worldwide – the story of a recording made over four decades ago. One recording sampled years after by Brian Eno and David Byrne, a sample she heard for the first time some 40 years later. Dounia’s voice accidentally had an immense impact on the art of sampling, DJing and even hip-hop. This is her story.

Road to Stardom

A natural born singer, Dounia’s love affair with music goes back a long way. She started singing in the church choir at the age of nine and slowly developed a growing interest in the bustling folk scene in Lebanon and the Middle East. It was around that time that one overheard conversation between her choir teacher and her parents changed everything. Dounia recalls: “She [her choir teacher] started telling them [her parents] all these stories about meeting the musicians and singers that I would hear on the radio. So I asked her: ‘Can you take me with you one day?'”.

Lebanon had one official radio station at the time, Radio Lebanon. It was the most important musical hub in the country – a place where every up-and-coming musician would go to showcase their talent, and hope to get the exclusive opportunity to record in their studios.

In what turned out to be an important “Bring Your Kid to Work” day, Dounia met the head of the music department at Radio Lebanon, Toufic el Bacha. El Bacha, himself a composer and musician, was one of the most important names in Lebanese folk music.

“They asked me to sing for him, so I did.” Dounia remembers his exact words: “This girl has a beautiful voice, I beg you, don’t let her go on without proper music education”.

Enrolling at the Lebanese conservatory opened many doors for the young girl. She played her first show at age 13, in a play titled Mawwal, and her performance in that gig impressed none other than Romeo Lahoud, another popular figure of Lebanese music.

Mawwal was on for a year, during which Dounia starred alongside big names like Samir Yazbek, Issam Rajji, Joseph Azar and famous dancer Nadia Gamal. “I was very proud to star in that show, and after that there was no going back.”

“I got a call from Assi el Rahbani one day.” Dounia says, recalling an encounter she had with the Rahbani Brothers, arguably the most important Lebanese musicians of that time.

“I went to audition for one of their plays. He asked me to sing ‘Ya rayeh A Kfarhala’. Mansour was there as well. They loved my performance and asked me to work with them.” Despite this, she chose to be honest with Assi: “Even though I would love to, I can’t work with you. You already have your stars, and you don’t need me”. For Dounia, the Rahbani world was already filled with famous singers and she didn’t want to join them to play a secondary role. Dounia’s ambition surpassed a lot of her contemporaries. She focused on the quality of the music she wanted to work on, aiming for the top.

Following Mawwal, Dounia went on to participate in the Cedar Festival, which hasn’t run in over 50 years. The young singer kept rising in the music scene, working with many big names of that era.

“Listen, the music scene can be very rough, especially for someone who doesn’t want to make a lot of compromises. I didn’t want to compromise. I couldn’t work with this person or that person just because they were in a position to push me higher. It was difficult, because I loved music in its purest form, deep down in my heart. I was not doing it to be famous.” Dounia explains further. “If someone spoke while I was singing, I would stop. I also refused to sing when there was food and drinks involved. I might be a purist in that sense, and to be an artist may require a different approach sometimes. Most people would have compromised. I didn’t.”

The day then came when Dounia had to make the most difficult decision of her career:

“In the early 70s, amidst that constant musical dilemma, I met my future husband. He was an army officer. In the army back in those days, you couldn’t have a wife in entertainment. I had to choose between music and family, so I chose to raise a family.” Music dreams and ambitions faded away, and Dounia’s career came to a halt.

Looking back at her career, two performances permanently marked Dounia’s name in the history of Lebanese music: collaborations with both Zaki Nassif and Wadih el Safi. But her signature song remains “Waynak Ya Jar”, the symbol of a timeless tradition in the Middle East: inviting a neighbor to morning coffee. The song is played on local radios to this day, though many people may not recognize the singer.

With Zaki Nassif, Dounia recorded “Da’a w Da’a Mchina” – a duet that takes listeners to lush countryside fields, and adds to present-day nostalgia for a country that has slowly been destroying its natural landscapes.

Dounia also starred in the musical “Tawahin el Leyl” with Wadih el Safi in the early 60s. The play stood the test of time, and can be enjoyed in the YouTube clip below:

The most mesmerizing part is around minute 44:20: Dounia’s rendition of Abou el Zelof, a standard in the world of Arabic music. A staple among many great Arabic singers (see Sabah), the song’s origins have been the focus of many music scholars throughout history. Unbeknownst to Dounia Younes, one of its renditions recorded in the early 70s would change her legacy forever.

The Forgotten Recording

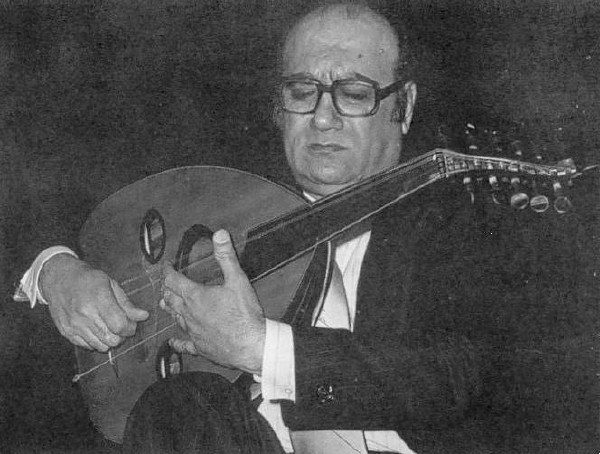

Dounia remembers taking part in a recording session in the office of Iraqi oud legend, Mounir Bashir in 1972, with the purpose of selecting a local singer who would participate in a festival for folklore music in Europe. Bashir wanted to send a-cappella recordings of Dounia’s voice to the festival organizers.

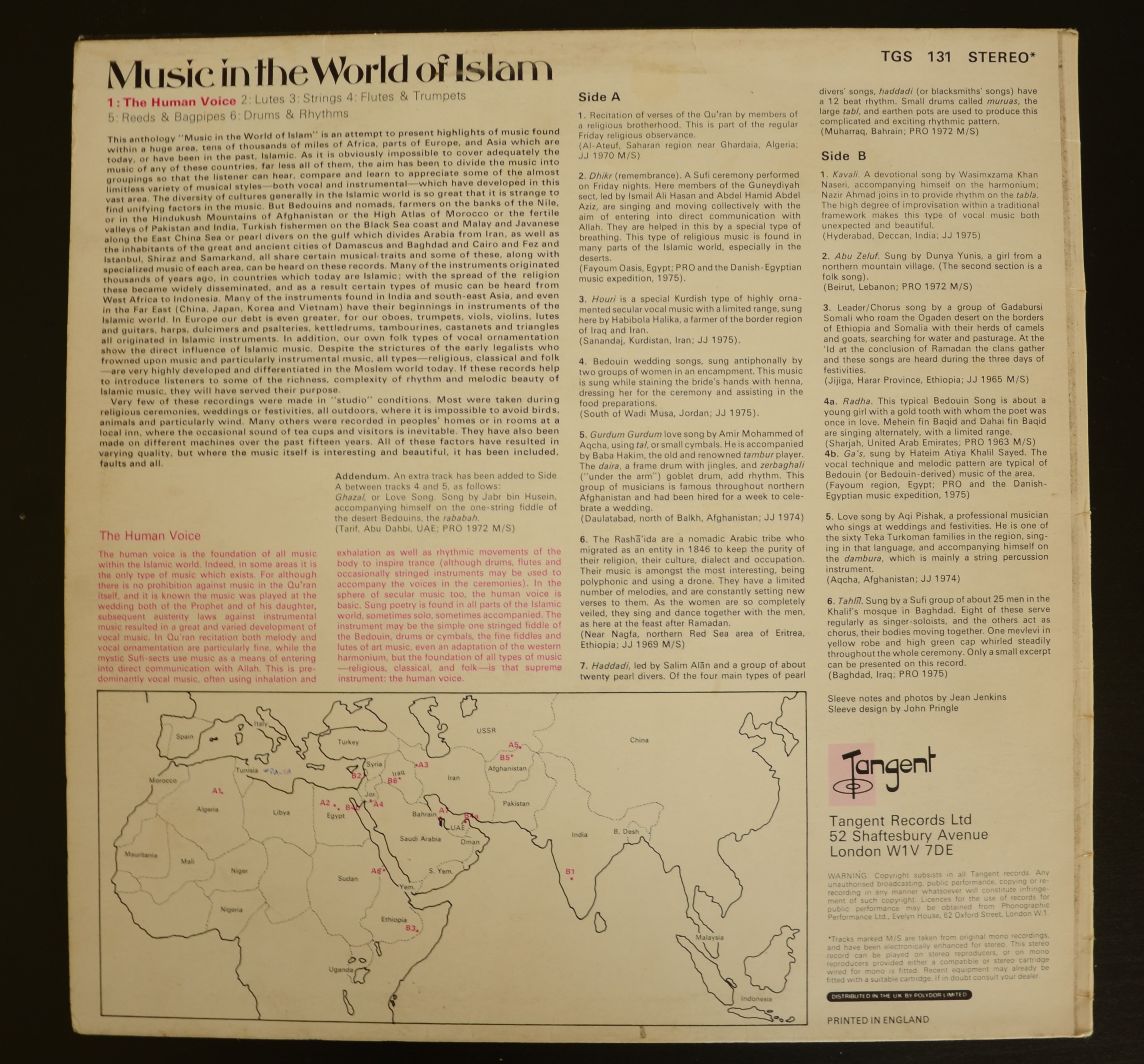

One eventually became commercially available, Abou el Zelof. It was featured in a 1976 compilation album titled Music in the World of Islam 1: The Human Voice edited by late Danish composer and ethnomusicologist Poul Rovsing Olsen and American ethnomusicologist Jean Jenkins. The compilation was the first of a series of six Music in the World of Islam releases, and featured vocal recordings from Egypt, Algeria, Iran and other Middle Eastern countries.

You can listen to the original recording below:

During their research for a 2006 paper titled Entangled Complexities1)Feld, S. & Kirkegaard, A, 2010, Entangled Complicities in the Prehistory of “World Music”: Poul Rovsing Olsen and Jean Jenkins Encounter Brian Eno and David Byrne in the Bush of Ghosts. PMP., professors Steven Feld and Annemette Kirkegaard gathered information from the diaries of the late Danish ethnomusicologist. According to them, Olsen recounted a trip he took to the Middle East in 1972 with the goal of recording local musicians and singers. Beirut had been Olsen’s first stop, where he came to be hosted by none other than Mounir Bashir.

It remains unclear how exactly the recordings of Dounia reached Olsen and whether or not they were handed to him directly by Mounir Bashir, but as Dounia would later confirm, it was done without her knowledge or permission.

Though not necessarily an astounding commercial success, the album Music in the World of Islam 1: The Human Voice was big enough to reach the hands of Arabic music enthusiast, British musician and producer Brian Eno.

Sample This

We’ll save you a Google search if the name is new to you. Brian Eno, who has been described as one of popular music’s most influential and innovative figures is mostly known for his pioneering work in ambient music. As a producer, his resume features names such as U2, Grace Jones, Coldplay, and Damon Albarn. His prolific discography also includes a number of influential albums as a solo artist, in addition to collaborations with David Bowie, John Cale, and David Byrne.

Eno incorporated sounds taken from The Human Voice in the World of Islam in a collaborative album with David Byrne, titled My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. Released in 1981, the album became a huge success, leaving behind a debated legacy on the use of sampling and the incorporation of sounds from “third world” countries. Having sparked substantial controversy (one track sampling Quranic recitals was removed following public uproar), the album eventually came to have an immense influence on electronic music and hip hop.

Eno & Byrne sampled Dounia’s vocals from Abou el Zelof in two different tracks on the album, “Regiment” and “The Carrier“. “Regiment” became the most successful and popular track on the album, receiving the biggest number of plays on the radio and across online music platforms.

While the use of sampling long predates the release of the album, Eno and Byrne’s approach was a pioneering one. My Life in the Bush of Ghosts was the first album to use sampling as a lead vocal, paving the way for decades of hip-hop innovations and elaborate electronic remixes. Pitchfork described the album as “both a milestone of sampled music and a peace summit in the continual West-meets-rest struggle” and along with Slant Magazine, listed it amongst the best albums of the 1980s. Rolling Stone reviewed the first issue as “an undeniably awesome feat of tape editing and rhythmic ingenuity“.

Sampling “exotic” voices may very well be a staple of electronic music today, but it wasn’t always the case. In the early 80s, this was a major innovation, and it inadvertently made Dounia the influential figure behind a mythical voice.

So little was known about that mysterious and titanic voice that rumors started to spread with the development of the Internet. Many Western listeners thought a boy was sampled on that track, others claimed it was Ofra Haza, the popular late Israeli artist.

Bringing the Record Home

As thousands of listeners discovered Dounia’s ceremonial voice in the original version of Abu El Zelouf and in “Regiment”, the “Lebanese mountain singer”, now a mother of three, had been leading an ordinary life with her family in Kfarhbab, north of Beirut. “Regiment” and “The Carrier” were completely unknown to her, and Dounia had no knowledge of any of the 1972 recordings being released.

It was during a visit to her home that we got Dounia to discover these tracks. This was essential in piecing the fragments of the story together and gathering her input which had been missing from the narrative for far too long.

Her face changed in disbelief when she learned that her rendition of Abou el Zelof was now two clicks away on YouTube. How could this have remained a secret for all these years? Her daughter Rayanne, who was present when Dounia listened to the recording for the first time, had always been keen to uncover her mother’s archive, whether it was through the Internet or the national radio. Those recordings had slipped her research, and at first, Dounia’s memory, though the singer slowly began to remember the details surrounding her collaboration with Mounir Bachir.

That day, everyone in Dounia’s living room held their breath when the needle dropped on The Human Voice in the World of Islam. For the first time, the mountain girl was listening to her own voice, her eyes full of emotion and nostalgia of what once was, and what could have been. For three minutes, her voice from 1972 filled the room, leaving everybody there in awe. There were a few seconds of complete silence after the recording stopped playing, before Dounia expressed melancholy for the voice she carried in her youth.

Dounia hadn’t heard of either Brian Eno or David Byrne and was very surprised by the story and the music brought to her home.

Original copy of the 1976 compilation

As she listened to both “Regiment” and “The Carrier” for the very first time, and although the style of music was not necessarily her favorite, she smiled and said: “They’ve been listening to my voice in the West for 40 years without me having any knowledge of it”.

Lost Rights

The story left everyone with many questions. How was the recording released without the knowledge of the artist? Who gave Eno and Byrne permission to use the sample? Was the duo aware of the story behind the original recordings? What rights do artists hold over field recordings?

Feld and Kirkegaard may have tackled some of these questions in their paper but they couldn’t find or reach Dounia at the time of the study and her whereabouts remained a mystery to them. A crucial part of the story was missing and as such, some of the issues they touched on in their research remained unanswered until today.

Any doubts raised in the paper about permissions granted at the time of the 1976 releases have now been cleared. Dounia and her family have confirmed that they never gave that permission and the recordings were indeed used and published without her knowledge or approval. In fact, Dounia had not been in contact with Bashir since the original recordings were made.

Other documents retrieved by the two scholars show that whether the artist was aware of the releases or not, there was no real compensation plan made regarding future sales of the record. The recordings were treated as being the property of Olsen and Jenkins, and Tangent Records, the label that released the compilation. The paper claims that neither Olsen nor Jenkins were consulted at the time, and Olsen only heard “Regiment” for the first time 6 months after its release. According to Feld and Kirkegaard, it made him uncomfortable due to the complexity of rights involved, and he worried about the embarrassment it could cause with Mounir Bashir. One might wonder if this reaction could also be due to him knowing that Dounia was never informed of the recording release.

According to the two scholars, EG Records, the label under which My Life in the Bush of Ghosts was released, eventually paid Olsen and Jenkins £100 for the use of the recordings in their album. It is rather needless to say that no penny from this small amount ever reached the artist, Dounia Younes. In one interview quoted in Feld and Kierkegaard’s paper, Brian Eno claims the only permission they got was from Tangent Records, as they couldn’t contact the Lebanese singer. Brian Eno was unavailable for comment on the matter.

The multiple stakeholders involved in this story, some of whom have long since been gone, and the complexity of the situation make it difficult to untangle the story’s copyright aspects. It seems like everyone involved in the original release and the subsequent sample were complicit to some degree. It also appears Dounia was conveniently hard to reach for all parties involved, and no one seemed to be bothered by the fact that her permission had not been given.

Legacy and Beyond

Although this article touches upon many characteristic issues of the music industry, its main purpose is to shed light on the career – and unintended legacy – of a talented young singer. Dounia Younes sang throughout her youth, uncompromising, and with an eye for perfection. Her name could have been up there next to those of other icons like Sabah and Fairuz, but she let love win, unaware that her voice would create ripples far beyond the Mediterranean coast. “Regiment” proved the power of sampling, not just as a complementary track, but as an alternative way of creating popular music from scratch. The success and reception of “Regiment” was a glorious manifestation of the marriage between East and West, and Abou el Zelof was the perfect sample. Following “Regiment” and “The Carrier”, many artists sampled Dounia’s voice in their work2)Santiago by Yello – 1987, Pump Up the Volume (UK Remix) by M|A|R|R|S – 1987, Angel Dust by New Order – 1986.

My Life in the Bush of Ghosts might be an influential creation, but it also raises many questions about the ethics of sampling, artists’ rights and permissions in the creative process and the appropriation of “exotic” Eastern folk in Western music. Boldly taking such freedom with someone’s art without their permission and without compensating them is reprehensible and should not be condoned, regardless of the creative opportunities it offers. Yet at the same time, what happened will have nonetheless immortalized Dounia’s voice for generations to come.

This story may have remained secret for years, but for many listeners, she will forever be the mountain girl with the mighty voice.

Researched and written by Bernard Batrouni

Edited by Natacha Feghali

References

| 1. | ↑ | Feld, S. & Kirkegaard, A, 2010, Entangled Complicities in the Prehistory of “World Music”: Poul Rovsing Olsen and Jean Jenkins Encounter Brian Eno and David Byrne in the Bush of Ghosts. PMP. |

| 2. | ↑ | Santiago by Yello – 1987, Pump Up the Volume (UK Remix) by M|A|R|R|S – 1987, Angel Dust by New Order – 1986 |