I’ve been spending a lot of time with my sister this quarantine and that’s something that rarely happens. When I first played Radio Alhara to her, she asked me “who’s this Ernesto Chahoud? I like him” listening to his debut set; so I explained to her about Funk and Disco, and about the Beirut Groove Collective, and then I realized that it was a first. I’ve never shared this part of my world or my relationship with this music with her before. This was also a first of many real conversations that were triggered by moments while surfing between the Yamakan pirate radios. I was being taken on several mindful, spiritual, and human journeys while listening. Little did I know that I was actually exploring an audio form of the founders’ ideal worlds, spaces they’ve recreated and reimagined for us to embrace and experience.

I had the pleasure of chatting with some of the people behind Radio Alhara, Hammam Radio, and Radio Al Hai to learn what they really sound like. You can read up on Hammam Radio in the interview we published here. We’re now at the 2nd part of this 3-part series, with Radio Alhara. Get to know it below:

“ I think the radio saved us. I mean, to suddenly enter a state of quarantine when you don’t even know what to do…”

That’s how the conversation started between me and three friends telling the story of their pirate radio. Rightfully battling to recall the exact dates of when it started (because dates collapse after weeks of confinement), they tell the story of Radio al Hara and how, similarly to its sister radios, it was inspired and facilitated by Radio al Hai from Beirut. We were on a group call between myself in Beirut, Yazan Khalili in Ram’Allah, Elias Anastas in Bethlehem and Saeed Abu Jaber in Amman; a bunch of people who could have hardly crossed paths physically, now connected through sound waves discussing music, counterculture, and COVID cures.

You guys have been at it for around two weeks, right? What does Radio Alhara mean to you now, as opposed to maybe a week ago?

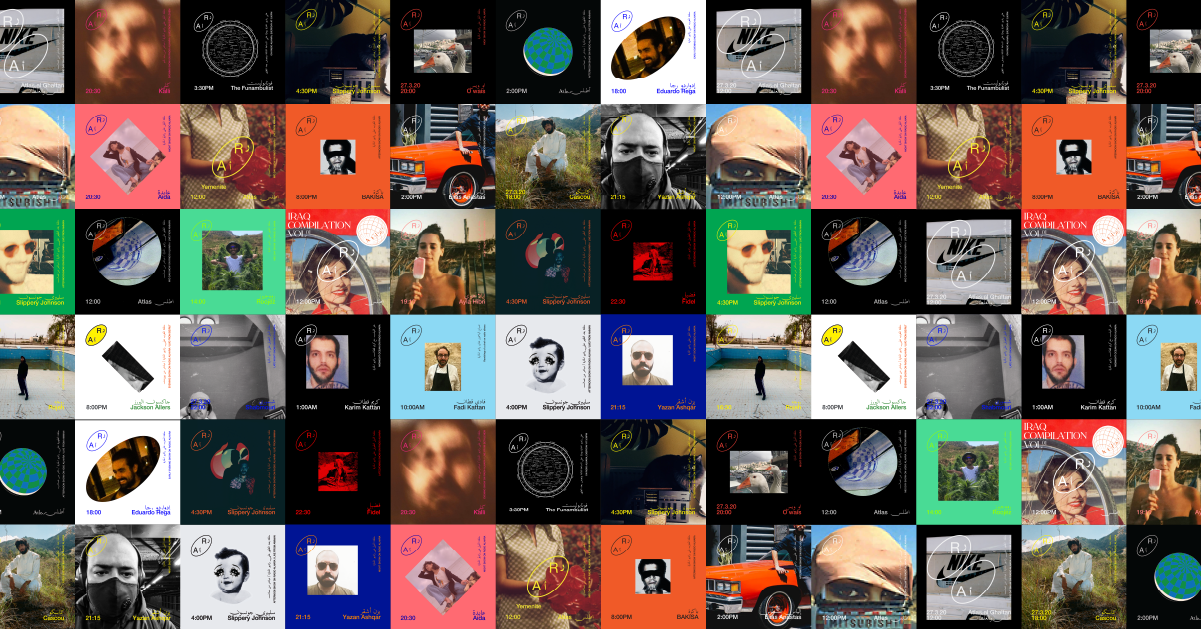

E: I’m seeing it more as a collaborative platform, it’s becoming an opportunity to look at different disciplines and ways of interacting with people from different areas, not just in the region but worldwide. Basically, we’re hosting people from different parts of the world, and the radio is acting more like a cultural center than just a regular radio. It’s trying to merge different cultural disciplines together. Right now, music occupies 70%-80% of our program but we’re gradually incorporating more cultural talk shows and podcasts. The idea is not to define the radio with a set identity, but to think of it as having a proliferating one.

…and how’s your journey towards that vision been so far?

E: I mean we’re getting more and more submissions on the radio from different musicians, artists, and researchers from everywhere. For example, we now have a regular podcast on the politics of space with the Funambulist Magazine published by Leopold Lambert in Paris. It’s focusing on finding a true moment of decolonization on a daily basis with guest speakers, which is a fairly broad question so we’re getting various responses daily.

Palestinians have been sharing and spreading Palestinian culture, art, and cuisine in communities around the world. Do you feel like Radio Alhara is another way of opening up to the world?

Y: We’re definitely opening up to the world, but not necessarily as Palestinians per se. I mean we are Radio Alhara from Palestine and Jordan now. I guess in these situations, Palestine is just like everywhere else. What we did was something more global and open to everyone. We directly received messages from people in South Africa, Canada, Japan, and from Europe and the Arab world. The internet kind of takes away from that locality; but at the same time, we are here. Our core network is mainly here and now we’re branching out. Our chef (Fadi Kattan, host of the daily cooking show Ramblings of a Chef) and dear friend is from Bethlehem, and he does share Palestinian cuisine, but the project is not necessarily about that; it’s just us being us—locals connecting with a global audience.

E: I think there are two layers to the name “Alhara”. On one hand, we feel Amman, Ram’Allah, and Bethlehem is basically one region, one neighborhood. Radio Alhara extends this vision on the scale of the planet. Because of the global quarantine and the internet, we’re all in the same setup and contexts so we’re trying to identify the whole world as one neighborhood.

I feel that, because of this pandemic as well as the nature of recent global movements, we’ve all been reminded of our global humanity and how we’re even more connected than we thought. The world has somehow opened up and started some kind of a global conversation. What do you feel is Radio Alhara’s contribution to it?

(Some reflective awkward silence)

Y:….. Saeed?

S: I feel everyone is online now, I mean we’ve always been online but now there’s a more communal sense to it. It’s just the nature of the situation we’re in, I guess…

Y: Maybe I’ll add that here in Palestine, we’re used to having imposed curfews, but usually we’re on our own in dealing with it. Now, the whole world has a curfew. Everyone has this abundance of time and people have this energy they want to make use of and direct. What Radio Alhara and other radios are offering is an effortless platform, it’s easy to set up your music and upload your files, and you just play. I think this abundance of time is a global state. I feel the success of our radio lies in how easy it is for anyone around the world to reach out to us and play their music. Plus, I think at the beginning of the quarantine and a bit before, many museums and art archives opened up and were uploaded for everyone to access and that was an interesting movement. But what really makes our radios different is that it’s a platform that’s also inviting more active participation. We’re asking people to be proactive and to bring forward any programs or shows or music sets they might have. It also lies in the nature of the medium itself; people listen to us while working from home. You cannot watch a movie while working, or cleaning, or cooking but you can listen—sound works differently. Our radios are filling up the spaces at home while you tend to your day in isolation.

E: Maybe it’s been more than 10 years since we’ve been having global conversations on climate change and the problems we’re facing in different countries around the world. Maybe this pandemic is an opportunity to take a better look at contemporary cultures in the city and to be able to create new formats of cultural exchange through the radio. With the possibilities of the internet and broadcasting, we get to question the way we do things and think of new ways of producing art that consumes less energy and is more respectful to nature; our radio is a platform that questions all these issues.

Are you curating your content to be able to introduce these new concepts and make room for these exchanges?

S: We were just talking about this yesterday! As far as content goes, we feel that, because there are more listeners tuning in now, we need to maintain a certain level of engaging content aside from the music. So maybe there is a bit of curation, but it’s still pretty fluid.

Y: We just started. I mean we are architects, designers, and artists; we’ve never worked in media or production before, as far as I know at least. It’s not about making it a radio that sounds like Monte Carlo, or other mainstream radios. The idea is how to make it a cultural center, as Elias mentioned earlier. A space where culture is exchanged, thought of, challenged and critiqued. The idea is to allow cultural practitioners to move through this radio and have space within it to create new things and challenge old ones; even to challenge how media works maybe. These radios might or might not survive the quarantine when it ends. But at least we’re starting a conversation around how to envision, from now, where we need to be post-COVID.

We notice a lot of uncut moments from the hosts and guest artists during streaming, like how rapper Haykal simply posted “sorry boys, my laptop crashed” during a cut in his debut live set, or when Youssef (host and co-founder) left his mic on longer than it should’ve been. How important is it for you to keep the radio somehow candid and uncensored?

Y: That’s exactly it. We are talking to you from the same environment that we record the radio shows from. My laptop is my studio, my son is in the next room. Now I’m doing this show on the economy (“A Helicopter Moment”) and I wait for him to go to sleep so that I can record; sometimes I would like to record while having him around because it depicts the actual reality of my situation. We’re at home, we are sitting, there’s nothing fancy going on—we use our personal laptops for broadcasting. I think we’re allowing this to seep into the radio to give it a kind of rawness and ease. Our motto is to make it from the bedroom to the living room and vice versa, passing by the kitchen, bathroom, balcony, window…I mean we’re also stuck at home, like everyone else.

From the sets you’re hosting to the playlists you have running, how diverse would you say your music is?

S: I feel it’s quite diverse at the moment, as far as genres and where the artists come from. You have Muthana Hussein’s (A.K.A Atlas) daily show, for example, he’s playing Yemeni, Khaleeji, sometimes North African music. I think a lot of genres are playing; I have a friend living in Portugal who just sent me that he now has us on all the time. I think this large variety of music keeps our radio fresh and this is what’s missing in the shitty radio stations we have on the FM. I mean if you alternate between a hundred FM channels in the car, you’ll die. Back when we used to drive cars at least…

… The way I see it in the future, it’s nice for it to be a platform that has a variety of content from music to talk shows and daily shows. It could be cool to have a platform that’s in some way curated by a collective; every one of us and the friends around us adds their own diverse and unique content to the overall mix.

E: I think the richness comes from the fact that it’s really open to anyone, which allows it to have diverse sounds and music coming from completely different parts of the world.

Y: It’s not mainstream. I mean since the beginning, we played a certain variety of music and people who liked it sent us their own music and got involved, so it organically created kind of a collective music taste. It’s just a radio that sounds like us; it’s a radio that I would like to tune into.

You have a pretty packed schedule of programs coming up, with artists and guest speakers from all over the region and the world. Are there any shows, programs, or surprises to look out for?

S: Well I think we, ourselves, are surprised every day! So I guess we’ll find out together.

Y: … In a week’s time, we’ll have a special cure for Corona.

Reaching the end of our chat and before we leave our readers with a message, is there anything that we’ve missed?

Y: I would say one thing definitely worth mentioning is the Radio’s visual identity. I feel Mothanna, Saeed, and Elias’s work on the visuals played a crucial part in the radio’s identity and success; maybe we can have a whole other conversation about its importance another time. I think for sure, the radio is a sound medium, but Radio Alhara’s unique visual identity and online presence really worked for us.

Some of the people reading this might be listeners of Radio Alhara or might tune in for the first time. Would you like to leave them with a message?

S: Yeah, maybe to just listen more. Try and open your ears to new things.

Y: Also, we want you to feel encouraged to contact us and work with us through the radio. To take it literally as an open space that you can collaborate with and experiment through.

Tune in here.