If you’ve ever had the pleasure of coming across one of Munir Khauli’s works, then you’ve found a treasure box of some of the funniest Lebanese rock and blues music videos of all time. Like most dark humor, Munir Khauli’s music is thoroughly drenched in truth, still relevant three decades later. “LOOK BACK, SEE AHEAD”, his YouTube cover photo says. With misery comes strength, but in Munir Khauli’s case, with misery comes humor.

Munir Khauli can be compared to the likes of Sixto Rodriguez, (who Searching for Sugar Man is all about). His low-budget videos, low-key presence, and ability to pick up a guitar and recite how society looks are what make Khauli one of Lebanon’s best social critics.

For now, Khauli is genuinely fed up. “Society will kill you before you change it.” His music speaks otherwise, still telling you what you need to hear: kitsch humor – where a joke is so bad, you’re left to question if it was intended to be. Unfortunately, sounding too much like Lebanon…

How old were you when you discovered your passion for music and writing? Did anyone in your family encourage you? Or was it a book or a song?

My musical start came from my mother, who made me and my two siblings take piano lessons at an early age. Soon after the piano (which I was never good at), I took up the guitar.

The radio was also very important to me while growing up. They used to play the top 50 hits of the 1970s; I was drawn to Elvis Presley and Chuck Berry, which steered me towards Rock ‘n’ Roll.

I am now 60 years old – looking back, I can safely say the blues have stayed with me longer than any other genre. It’s all fascinating and moving but if the blues creep into you, they stay there forever.

I read you studied English Literature at AUB – what were some of your favorite books?

I was in love with the Arabic language and wanted to study Arabic literature, but I don’t remember why it wasn’t doable. I enjoyed English and it is probably the Romantics that had a hand in shaping my career. My favourite poet at the time was John Donne – I still remember images from his poetry ‘til today.

How did the Romantics mold your career?

Studying English Literature and falling in love with John Donne’s poems – that wasn’t good for me; I fall in love easily, but not out of love easily. My earliest songs were composed in the spirit of Bob Dylan, at the time. You sing folk to speak your mind, and you play rock to swing and have fun. But once the Civil War started and I had to immigrate to California; my love songs were thrown aside and replaced by Arabic songs, to address the issues of Lebanese society and the war.

You’ve mentioned in an interview that you feel like an outsider, where or how do you find yourself fitting in most in society?

I definitely am an outsider; the way I live my life is on the fringes of society. It stems from my disdain of society (I consider the human being a failed project). I said clearly in one of the shorter interviews on YouTube (those are the shorter ones because they don’t want to hear you diss mankind in general on TV): humans think they are entitled to everything that grows and moves. I don’t like that at all. I am more comfortable outside of this whole system. How can you respect human beings if you are not a typical human being?

Going back to the Romantics, I would have been happier being born in the ‘20s in an English countryside or in the Old Ages with a loincloth and beard.

I have an idea of the things that make you angry, but what makes you happy?

Less and less things these days – it’s a difficult time for everyone… But if you’re a metropolitan person like me, where we cross paths with few or no animals in our daily lives, then seeing a bird finding crumbs and eating them is one of the things that makes my day.

I am also a fan of Arabic TV shows. It’s a hobby of mine to record and collect them.

What type of Arabic TV do you enjoy collecting?

Mainly comedy from the 1960s and 1970s. “ShouShou” (Hassan Alaa Eddin) died too early and didn’t have a chance to do a lot, but I have all 13 years of his career recorded and saved. I wanted clean copies to watch whenever I please, so I started by recording them on VHS, then moved them to DVD, modified the output, and now have the whole collection on digital.

Duraid Lahham and Nihad Qali, the icons of Syrian comedy, are also part of my collection. Syrian comedy was ahead [of Lebanese comedy] by many years, in terms of humor. The Lebanese are good at making fun, but Syrian comedy was pure.

Which is very much what I hear in your lyrics and videos…

Give me one adjective, and comedy comes first. There is a difference between cracking a joke and narrating a joke. When you crack a joke, you are making it on the fly. I also like to use “kitsch”, which is when comedy is so bad it makes you wonder if it was actually intended to be like this… I made two documentaries – I would very much like to think they are kitsch.

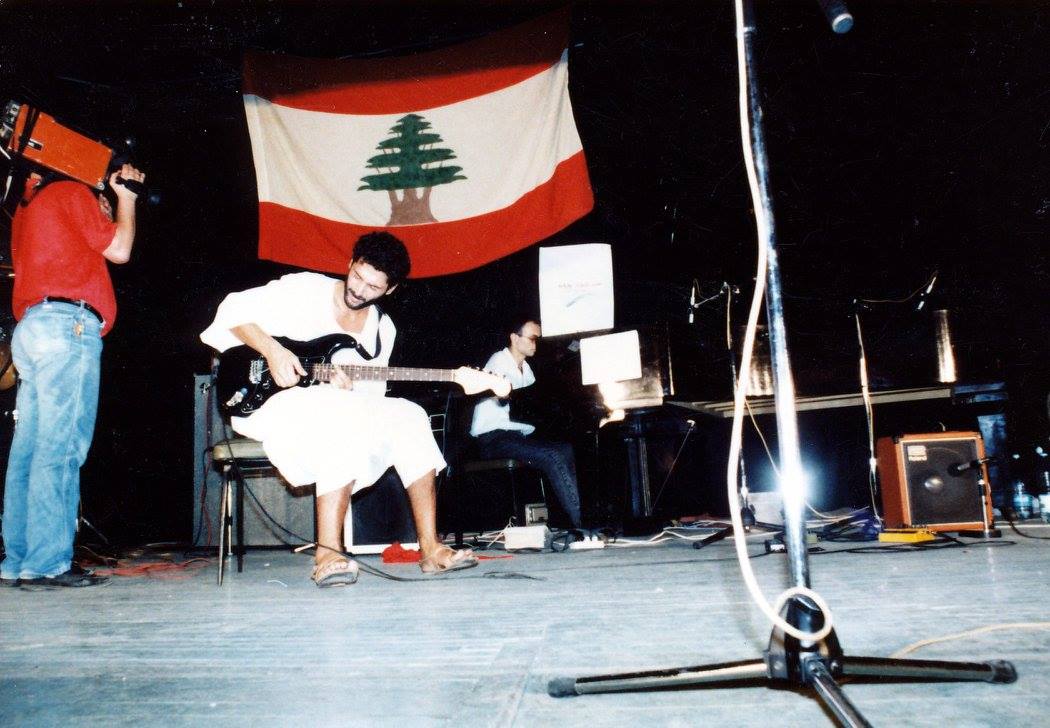

What was your most memorable performance?

I only got the chance to be on the stage a few times (around 20 I think), so every performance was memorable. In 1988, I did two nights at AUB where the whole performance was filmed on TV. I felt audiences were amazed, listening to a new genre and way of songwriting they hadn’t heard before… The feedback was great.

Once it rained on us during the second song of my performance, and I asked a friend to throw me some goggles onto the stage so I put them on as a photo op.

Along with using onomatopoeia, filming, and Russian military drums, what other elements of your music creation have led you to diverse places?

I like a piece of work to be direct and effective in what it’s trying to say and to whom it is targeting. While making music I found using mixed media, which sometimes feels contradictory (who isn’t?), to bolster the lyrics. I found mixed sounds from TV or elsewhere to be very appealing to me, like in one of my tracks “Zit Basleh”. If you wear proper headphones you can hear how extensive the use of sound effects is in order to push what the narrator is saying.

Onomatopoeia, as we go back to English literature, gave me good rhyme and rhythm. In music, I consider myself a craftsman by learning to maneuver a song to get to people. I don’t consider it a work of art or “larger than life”, as musicians tend to be portrayed (especially in the West). I like to think of a musician as a guy in a workshop with a paper and pen and maneuvering things to make a product with all its parts delivering the end product effectively.

What effect were you trying to achieve?

As a Lebanese [person], I grew up hating the war and the effect it had on the nation so I used music as a weapon to direct messages to the general public in hope that one would feel relieved. There is comfort in hearing stress being expressed in a light way. Writing songs as a way of righting wrongs (and this is a summation of my reason for writing and recording; to right the wrongs I see in this country). Some of my songs are like a sermon, as a fan told me once. If I didn’t have a message I would go back to singing blues, but I am a guitar player in the coeur; I was angry so my music came as a reaction to the civil war, and probably go again. I didn’t want to go without saying my piece, and I decided to put my ideas in music.

Frank Zappa was a huge influence on my music. He was so prolific; he’s been dead 20 years but albums still come out (over 100 albums and still counting). He was a social satire mouthpiece, he made fun of America, and was the ultimate social critic; he did it through songs instead of essays. There are ways to change society – using and creating sound effects could be one of them.

How has your writing or lyrics evolved over the years? Have you noticed any changes?

I was much angrier when I first started writing but I used humor to convey the anger. Age has mellowed me now. In terms of songs, I found a custom-made formula that fit the mood I wanted to create very well in 1985 and stuck with it throughout my career, so you wouldn’t notice a huge style change in my songs; similarly to how most artists maintain the same tone during their entire career, like Bob Dylan, for example. Fans don’t want them to change style. I’m the guy with a message – if I find it is effectively received through my music, I won’t change it.

Even though I was singing in Arabic, I’ve always wanted the guitar to say its piece. If you study my music in that angle you will find a lot of variety in what my guitar had to say (as you might be able to tell in “Ma Kbir Ila Jamal”).

You’ve mentioned how liberal Lebanon is – does this come with any challenges?

Watching the revolution now and being a true liberal is indeed challenging. Lebanon in many ways is still a very old-fashioned society. My feeling is that if you study the demographics of people who go for a career in the police, government, or state department, you will find a great deal of them with a village mentality, being out of line with youth culture.

Being on the streets today I still see the disparity between the two groups, where neither one can understand the other. Unfortunately liberals are still the minority.

If you could amend the constitution what laws would you change first?

I’m not a good authority for this question as I don’t know the laws in the constitution. I would think what’s lacking is that the majority of laws have not been applied – that’s why we think they don’t exist. I am sure I won’t see the day we will see them applied. Our politicians are tacked so firmly to their chairs in the parliament; it is up to the new generation to find a way to uproot them.

I’ve read you spent time in Berkley, California. What do you think is important to remember as a Lebanese expat? Do you have any advice for the many expats/Lebanese people living abroad?

The first advice that comes to mind is to stay there.

When I first went to America, it took me years to stop being Lebanese in order to become a man of the world. You need to shed some skin first.