Beirut, the early 1960s: a time of growing religious and political tensions in and around Lebanon… But something else was brewing then: the rise of rock & roll. Circa 1964, the Beatles erupted unto the international scene and the entire world, the Middle East included, fell for their music (and their boyish charm).

With the Fab Four’s breakthrough, Lebanese and Arab bands playing psychedelic and garage rock started to emerge in the 1960s and 70s: Dark Eyes, The Kool Kats, The News, The Nomads, the Vultures… catchy names that have since been forgotten, and whose music is sparsely found on the Internet today.

But one of them – the very first rock act to emerge in Lebanon as early as 1962, deserves a special mention. In turn called “Top 5” and “the Sea-Ders,” their music masterfully incorporates the Byrds’ psychedelic harmonies and the distinctive vocals of the Beatles’ front men… with an Oriental twist [editor’s note – don’t just take our word for it: check out the band’s comprehensive playlist at the very bottom of the page and listen while you read]. This is the story of a band that broke cultural and religious barriers, landed a major deal in London during the swinging 60s and one day caught the eye (or ear, rather) of a couple of guys named Paul McCartney and George Harrison. This is the story of the Lebanese rock band that maybe, just maybe, could have made it big on the international stage.

By Linda Abi Assi and Bernard Batrouni

The early days

We tracked down the Sea-Ders’ drummer, Zouhair Tourmoche, better known by his stage name, Zad Tarmush. More than 40 years after the band’s dissolution, he still goes around fervently commenting on YouTube videos of their songs, even once taking the time to correct a YouTube user who had the audacity to claim they hailed from Israel.

He doesn’t need much convincing to reminisce about the past, starting with his teenage years in Beirut’s Ain El Mreysseh.

“In those days, I used to hang around and wait for the girls to come back from school,” he remembers. “I had a friend who one day warned me that I couldn’t spend my entire life picking apples and waiting for girls to smile at me…. And that I should try studying music instead.”

So Zad took up drumming at the Saliba School of Music on Sadat Street, in the Ras Beirut district. “It was very cheap. I’d pay 25 liras a month and I’d study drums every day.”

He met the other band members in 1961. “Back then, in the late 1950s, early 1960s, there were no radio stations playing rock & roll in Lebanon.” Instead, he eagerly waited to listen to Radio Cairo on Friday nights, hoping to catch his favorite band, Cliff Richard and the Shadows.

A young Zad in Beirut (1962)

“I was hanging in a music store one afternoon and in came these two short guys, Raymond Azouri and Joe Shehade. Fats Domino’s “Blueberry Hill” was playing and I started drumming along to it on a wooden bench. Ray and Joe were impressed that I could keep up with the rhythm, and they asked me to join their band.”

Zad didn’t hesitate for long. “I knew these guys, they were talented. They’d once been on Lebanese TV, and they used to sing songs by the Everly Brothers with perfect pitch and harmony. They sounded exactly like the original artists.”

“So at the age of 16, I stopped going to the mosque to pray to Allah and rock & roll entered my head in a very big way.”

By 1962, the guys went by the name “Top 5” (with Raoul Hajj and Joe Samaha on lead and bass guitar respectively) and became the first ever rock band to appear on stage in Lebanon. They had their roots in late 1950s and early 1960s rock, inspired by acts like Elvis Presley, Cliff Richard & The Shadows, Roy Orbison, Del Shannon, Bobby Vee, Paul Anka, Johnny Hallyday and Neil Sedaka.

Top 5 soon developed a following, performing in hotels and universities in Beirut and, on weekends, in special clubs where there were no drugs and alcohol allowed, “just Coca-Cola and good old rock & roll music.”

Top 5’s first gig at the American University of Beirut (1963)

Rock & roll meets Islam

The 1960s saw profound transformations both in Lebanon and the region: the rise of Nasser’s Arab nationalism, heavy Palestinian migration into the country and latent repercussions of the short-lived 1958 civil war. It was in this context that the band came about, but with no particular message in mind. “While people were talking about politics and religion, we didn’t get involved. All we wanted to do was play music,” says Zad, who remembers noticing a “naïve disapproval of each other” but only among “simple-minded people.”

Still, he recalls the country being structured along two distinct groups: Muslims and Christians. “If you were born Christian, you’d tend to suffer little or no hassle if you followed a musical career inspired by European influences. However, as I was the only Muslim in the band, I had to endure a great deal of insults, verbal abuse, and all other forms of stupid prejudices, all of which were hinged on one idea: that a decent Muslim boy would never abandon his culture and follow decadent Western behaviour.“

Early on, he remembers being given a lot of grief about his penchant for all things “Western.” “In 1959, I bought my first pair of James-Dean-inspired blue jeans and became the target of a disapproving neighbor, who tried to beat me up,” he recounts. Another target, later that year: Zad’s hairdo. “I had an Elvis Presley-like fringe. One day, my older brothers lectured me about abandoning my culture and dragged me to our local barber who, in turn, gave me a “shit-jibe” on how to be a good Muslim, all the while butchering my Elvis Presley hair.”

Zad with a Canadian fan in a Beirut night club (1965)

The British invade the Middle East

But 4 years later, in 1963, “Please Please me” hit the charts and Zad had a new reason to change his hairstyle again, as Beatlemania swept across the world like a tsunami.” “Luckily, I had a nose like Ringo Starr,” he jokes. “We decided to grow our hair long and we looked just like them.”

Zad says the Beatles revolutionized them completely, and opened the door to other bands like the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, the Who, the Grateful Dead, Bob Dylan, The Byrds, The Faces, Cream….

“That year, there was a cinema in Hamra where they showed the film “A Hard Day’s Night” and the owner asked us to take the stage 20 minutes before every séance to sing Beatles songs.”

So Zad, Ray and Joe dropped their old repertoire, polished their “ooohs” and “yeah yeah yeahs” and perfected their little headshake. “We felt like we had made it.”

From that moment on, they made a name for themselves in Lebanon as skilled “imitators,” capable of replicating the Fab Four’s sound (and looks) down to a T. “They even called us “the Beatles of Lebanon,”” Zad recalls.

Top 5 doing their best Fab Four impression at a ‘Hard Day’s Night’ showing in Hamra (1964)

London calling

In 1966, the band started to write their own stuff. “Ray and Joe cobbled up a deal for us to produce our own record in Lebanon,” Zad explains. “This is where the politics come in, which I did not entirely agree with,” he adds. The band’s first offspring, “Thanks a Lot,” went on to sell well in the country.

But Zad wasn’t part of the decision-making process. “I was the shy musician in the back, I just went with the flow”… a prelude to the rest of the band’s career, during which he never interfered with internal politics.

But with the song getting a good reception in Beirut, things started to turn. The record ended up on the desk of a man named Dick Rowe at London’s Decca Records, who promptly offered to sign them. Interestingly enough, Rowe is infamous for rejecting the Beatles, even though he displayed a tad more flair when he later signed the Rolling Stones.

In August of 1967, the band was ready to leave Lebanon. “We had spent almost 5 years revolutionising the Lebanese rock & roll scene, we challenged our traditional society with our long hair and our frayed bell-bottom blue jeans, we endured much criticism for adopting a Western style, and as more and more local bands were starting to emerge, we decided to explore new musical frontiers,” Zad explains.

… All with a brand new name: The Sea-Ders, a decidedly Lebanese name, as the band started to veer into a more “Oriental” direction. Raoul Hajj and Joe Samaha left before the big move and in came lead guitarist Albert Haddad to replace them, with Ray taking up the bass.

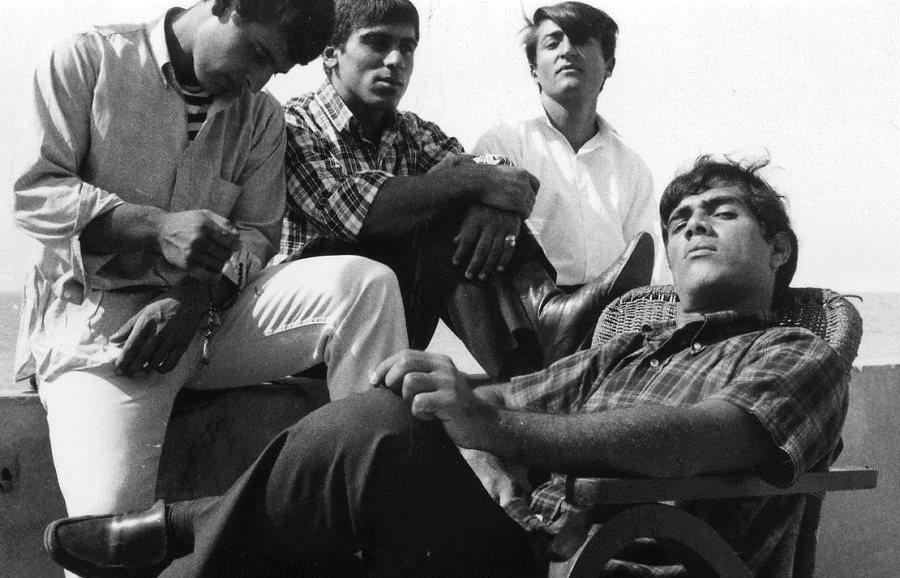

The Sea-Ders’ new lineup (1966). From left to right: Joe, Zad, Albert and Ray.

Albert Haddad also happened to be a good buzuq player, an instrument that soon became ubiquitous to the band’s sound. “It wasn’t intentional,” Zad explains. “We wanted to be a true rock band and never once thought of adding an Oriental twist to our music. In those days, people in Lebanon thought that anything that wasn’t Western wasn’t worth listening to.”

“We didn’t really have the feeling that we had to promote our culture,” he adds. “We were young, we were hippies and we felt like we belonged to the entire world culture.”

But the producers at Decca had different plans. “From the get go, they told us: look, you’re Lebanese so play Oriental music.” Knowing full well the kind of questions they could expect in London at the mention of their nationality, the guys made sure to bring along a picture of them posing in Baalbeck surrounded by camels… Testament of their new (reluctant) status as “Arabs.”

“One of the Decca producers suggested we use the buzuq in our songs, so we did,” explains Zad. The band quickly attracted some attention. During a 3-month gig at the PickWick, a club in Leicester Square, actors Victor Spinetti and John Hurt even came down to hear them play. And then there was the night Paul McCartney and George Harrison stopped by to see the band playing “this weird instrument.”

The Sea-Ders released “For Your Information,” their first single in the UK, in 1967. But the record never made it to the charts. Still, Decca followed it up with the release of an EP, which included 8 original songs. “It was a complete and utter failure,” says Zad. “To this day, people tell me it was a fantastic record, and that we were really avant-garde. But in all humility, I tell them: “hey, we failed.””

Why such a flop? According to Zad, it’s all about luck in the music industry… But sometimes, he adds, it’s also about knowing the right people. “For instance, there’s a rumor going around that when the Beatles released “Love Me Do,” Brian Epstein bought all the records himself, to make sure it would do well in the charts.”

The Sea-Ders in Baalbeck (1966).

Sex, drugs and rock & roll?

In the 1960s, rock & roll became associated with a much less inhibited attitude toward drug consumption, especially among musicians. But Zad candidly swears he was never tempted by it. “We were turned on by the music. A lot of people don’t believe me, but this is why, at 68 years of age, I look like I’m 29 going on 30,” he laughs.

Even after the move to London, the band remained impervious to illicit substances. Thrown into a whole new world, Zad says he was “scared” at first. “Everyone was taking LSD and acting weird. We kept a semblance of reality, maybe because we were brought up in a different culture. I don’t think any of us ever touched that stuff.”

After their EP’s commercial failure, Zad’s memory becomes a little fuzzy (evidently, drugs had nothing to do with it). “I think we made a second record, followed by another thing…. And then we disbanded,” he quickly sums up. The reason for the band’s dissolution is unclear but Zad hints at a disagreement between the four of them, saying they “fragmented from within.” In 1969, with their visa coming to an end, Ray, Joe and Albert returned to Lebanon but Zad decided to stay in the UK.

“We came out of Lebanon happy, successful and capable of imitating great bands, and when we got to the UK, we were told to do this and that… We didn’t have the anchor to take our vision further,” he laments.

After 1969, Zad decided to hang up his drumsticks. He became a British citizen in 1974, and made a living working as a schoolteacher. He’s still playing music, mind you, only he’s doing “modern” stuff. And in more than 40 years since the band’s implosion, he’s severed all ties with his former band mates… and his home country, for that matter.

So what went wrong exactly? Looking back at their short-lived career, their glory days in Lebanon, playing songs that weren’t theirs, and their (forced) foray into a more Oriental sound in high-flying London, Zad feels like that latter musical shift nipped their growth in the bud. “We should have explored other musical areas – like jazz-fusion, heavy rock and heavy metal, which were the next logical developments after the Beatles. That’s what bands like Cream, Jethro Tull, Vanilla Fudge or Jimi Hendrix were doing at the time.” Zad also cites bands like Led Zeppelin and Dire Straits as examples of the direction the band should have taken.

Could the Sea-Ders have succeeded? After all is said and done, it feels like a serious case of wrong place, wrong time. Still, they boast an impressive track record and leave behind a remarkable, albeit limited collection of songs … and a whole lot of wasted potential.

More crumpled black and white pics, funky outfits and 1960s hairdos right this way:

(To give credit where credit is due: some of these pictures were taken by Gaby Saade, the band’s manager from 1961 to 1966; others were taken by Richard Howes, their manager in 1967 and 1968. The rest were taken by friends and members of their entourage.)

And listen to The Sea-Ders’ music here:

To listen to some of Zad’s recent stuff, click here.